Blurring The Boundaries of Science and Art

The Huang Fellows virtually visit the North Carolina Museum of ArtWhen I think of art, I immediately think of drawings, paintings, music, and dance. Rather than simply looking at or listening to a piece of art on the surface level, there exists a separate universe where the audience can experience emotional feelings and thoughts from the artist, while also shaping these ideas into new ones that are more personal. Through virtually visiting the North Carolina Museum of Art and meeting with art conservators Corey Riley and Perry Hurt, I enjoyed learning about the applications of science in preserving art which changed my overall perception of art.

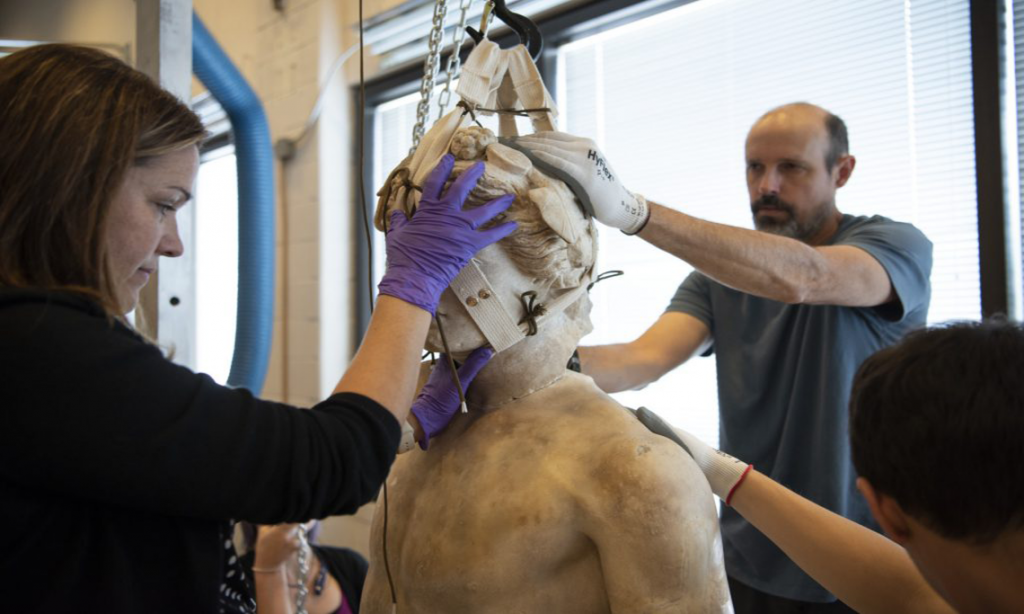

The Bacchus Conservation Project studied the history of a specific statue known as Bacchus. Ms. Riley explained the exploration of Bacchus as looking into the technical art history in terms of what, how, and when he was put together.

To my surprise, scientific terms such as gamma radiography and isotopic analysis would begin to merge into the conversation. Gamma radiography was used to investigate how Bacchus was put together. Stone scientists utilized isotopic analysis which involves taking powdered marble samples to investigate where the quarry came from. The isotopic analysis results revealed significantly different locations where each part of Bacchus is originally from. To answer the question of when Bacchus was put together, materials scientists provided their expertise in analyzing and dating the materials that Bacchus is composed of.

Beyond analyzing the technical art history of Bacchus, Ms. Riley emphasized the essential collaboration with scientists in the process of art conservation which consistently includes de-restoring and re-restoring. The consideration of taking apart Bacchus was largely guided by structural engineers and science to understand what would collapse in different situations. For example, if structural engineering suggested any risk of the legs collapsing upon taking off the torso, Ms. Riley and other art conservators would not take the risk. The process of reconstruction also meets scientific research with regards to identifying correct adhesives and correct positions.

While Ms. Riley discussed object conservation, Mr. Hurt led us on another journey into the conservation of paintings. Similar to the analysis of Bacchus, the technical art history of paintings is largely science-based.

Finding answers to the questions of who created the painting as well as when and where the painting was created lies within conservation and scientific treatments. Mr. Hurt explained how infrared technologies including ultraviolet imaging are used to see beyond the surface to get insight into the artist and their decision-making, while gas chromatography and mass spectrometry are used to identify the medium of a paint.

In one case, Mr. Hurt showed us a painting of a man where conservation treatment revealed the various changes made to the jacket collar. The initial collar was different from the final collar seen without conservation treatment. The prominent influence that various areas of science have on art conservation is astonishing.

Ethical questions of art conservation remain complicated. However, Ms. Riley and Mr. Hurt emphasized their efforts to bring back history rather than to disguise history in art conservation. If something was added on to the original piece of art, such as a new arm for Bacchus, they clearly publish that the arm is theirs and not a part of the original art.

The interdisciplinary work between a large group of scientists and art in the case of conservation is fascinating as the analytical knowledge from scientists combined with the knowledge of art conservators ensures greatest effectiveness and security in preserving historical art. Ms. Riley and Mr. Hurt described being very conscious and open about what is trying to be accomplished in discussions with scientists as clear communication ultimately benefits both sides. In general, scientific communication is incredibly important as we have learned in many other seminars and activities in the summer program and is relevant for Ms. Riley and Mr. Hurt as art conservators.

Artists create the piece, while scientists and conservators help to preserve it. Working together, the defining boundaries of science and art become blurred which I find particularly exciting as an art enthusiast and aspiring scientist myself.

Amy Guan, Huang Fellow ’24

Amy is a first-year student from Ames, Iowa, and is planning to major in biomedical engineering on the pre-med track.

Amy is a first-year student from Ames, Iowa, and is planning to major in biomedical engineering on the pre-med track.